|

He Who Goes to Law Takes a Wolf by the Ears |

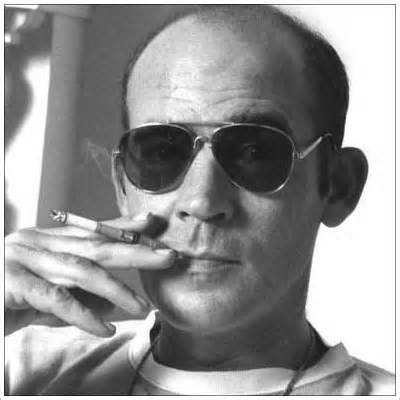

Hunter S. Thompson

I am not a criminal defense lawyer, but I have what they call "a very strong background" in the criminal justice system, and much of that background is based on extremely personal experience. I have taken that wolf by the ears many times, and I have learned many powerful lessons along the way. It is not the most desirable and certainly not the most efficient means of gaining an education in law. I would not recommend it for my son, for instance, or for anyone else's children. There is no prestige in it, and sure as hell no money. It is like getting an education in electricity by wandering around in a lightning storm with a long steel rod in your hands.

I have known a few jails in my time, and I have been in many courtrooms for many deeply disturbing reasons. My parents were decent people and I was raised, like my friends, to believe that the police were our friends and protectors — the badge was a symbol of extremely high authority, perhaps the highest of all. Nobody ever asked "Why?" It was one of those unnatural questions that are better left alone. If you had to ask that, you were sure as hell guilty of something, and probably should have been put behind bars a long time ago. It was a no-win situation.

My first face-to-face confrontation with the FBI occurred when I was nine 9 years old. Two grim-looking agents came to our house and terrified my parents by saying that I was "a prime suspect" in the case of a federal mailbox being turned over in the path of a speeding bus. It was a federal offense, they said, and probably carried a jail sentence.

Mailboxes were huge back then. They were heavy green vaults that stood like Roman mile markers at corners on the neighborhood bus routes and were rarely, if ever, moved. I was barely tall enough to reach the mail-drop slot, much less big enough to turn the bastard over and into the path of a bus. It was clearly impossible that I could have committed this crime without help, and that was what they wanted: names and addresses, along with a total confession. They already knew I was guilty, they said, because other culprits had squealed on me. My parents hung their heads and I saw my mother weeping.

I had done it, of course, and I had done it with plenty of help. It was carefully plotted and planned, a deliberate ambush that we set up and executed with the fiendish skill that smart 9-year-old boys are capable of when they have time on their hands and a lust for revenge on a rude and stupid bus driver who got a kick out of closing his doors and pulling away just as we staggered to the top of the hill and begged him to let us climb on....

He was new on the job, probably a brain-damaged substitute, filling in for our regular driver, who was friendly and kind and always willing to wait a few seconds for children rushing to school. Every kid in the neighborhood agreed that this new swine of a driver was a sadist who deserved to be punished, and the Hawks A.C. were the ones to do it. We saw it more as a duty than a prank. It was a brazen insult to the honor of the whole neighborhood.

We would need ropes and pulleys and certainly no witnesses to do the job properly. We had to tilt the iron monster so far over that it was perfectly balanced to fall instantly, just as the fool zoomed into the bus stop at his usual arrogant speed. All that kept the box more or less upright was my grip on a long, "invisible" string that we had carefully stretched all the way from the corner and across about 50 feet of grass lawn to where we were crouched out of sight in some bushes.

The rig worked perfectly. The bastard was right on schedule and going too fast to stop when he saw the thing falling in front of him. The collision made a horrible noise, like a bomb going off or a freight train exploding in Germany. That is how I remember it, at least. It was the worst noise I'd ever heard. People ran screaming out their houses like chickens gone crazy with fear. They howled at each other as the driver stumbled out of his bus and collapsed in a heap on the grass. The bus was empty of passengers, as usual at the far end of the line. The man was not injured, but he went into a foaming rage when he spotted us fleeing down the hill and into a nearby alley. He knew in a flash who had done it, and so did most of the neighbors.

"Why deny it, Hunter?" said one of the FBI agents. "We know exactly what happened up there on that corner, on Saturday. Your buddies already confessed, son. They squealed on you. We know you did it, so don't lie to us now and make things worse for yourself. A nice kid like you shouldn't have to go to federal prison." He smiled again and winked at my father, who responded with a snarl: "Tell the Truth, damn it! Don't lie to these men. They have witnesses!" The FBI agents nodded grimly at each other and moved as if to take me into custody.

WHACK! Like a flash of nearby lightning that lights up the sky for three or four terrifying split seconds before you hear the thunder — a matter of Zepto-seconds in real time — but when you are a 9-year-old boy with 2 full-grown FBI agents about to seize you and clap you in federal prison, a few quiet Zepto-seconds can seem like the rest of your life. And that's how it felt to me, that day, and in grim retrospect I was right. They had me, dead to rights. I was guilty. Why deny it? Confess now, and throw myself on their mercy, or what? What if I didn't confess? That was the question. And I was a curious boy, so I decided, as it were, to roll the dice and ask them a question.

"Who?" I said. "What witnesses?"

It was not a hell of a lot to ask, under those circumstances — and I really did want to know exactly WHO, among my best friends and blood-brothers in the dreaded Hawks A.C. had cracked under pressure and betrayed me to these thugs, these pompous brutes and toadies with badges and plastic cards in their wallets that said they worked for J. Edgar Hoover and they had the right, and even the duty, to put me in jail, because they'd heard a "rumor in the neighborhood" that some of my boys had gone belly up and rolled on me? What? No. Impossible.

Or not likely, anyway. Hell, nobody squealed on the Hawks, or not on the President, anyway. Not on me. So I asked again: "Witnesses? What witnesses?"

And that's when I first grabbed that wolf, folks. I had no choice. It was self-defense. I didn't want to do it, and I sure as hell didn't plan to, but he got too close to me and he smelled like death, so I seized him — and everything since then has been like a chain-reaction, a series of finely connected explosions.

We never saw those FBI agents again. Never. And I learned a powerful lesson: Never believe the first thing an FBI agent tells you about anything — especially not if he seems to believe you are guilty of a crime. Maybe he has no evidence. Maybe he's bluffing. Maybe you are innocent. Maybe. The law can be hazy on these things. But it is definitely worth a roll.

"Were it made a question, whether no law, as among the savage Americans, or

too much law, as among the civilized Europeans, submits man to the greatest

evil, one who has seen both conditions of existence would pronounce it to be the

last; and that the sheep are happier of themselves, than under the care of

wolves."

- THOMAS JEFFERSON, "Notes on the State of Virginia," 1784

Dr. Hunter S. Thompson's books include "Hell's Angels," "'Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas," "Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail '72," "The Proud Highway," "Better Than Sex" and "The Rum Diary." His new book, "Fear and Loathing in America," has just been released. A regular contributor to various national and international publications, Thompson now lives in a fortified compound near Aspen, Colo.